Winner, Best True Crime, Ned Kelly Awards, 2015

Winner, Western Australian Premier's Book Award, 2016

Shortlisted, Indie Book Awards 2015

Shortlisted, NSW Premier's Literary Awards, Douglas Stewart Prize for Non-Fiction 2015

Shortlisted, Prime Minister's Literary Award for Non-Fiction, 2015

Longlisted, Stella Prize, 2015

Anyone can see the place where the children died. You take the Princes Highway past Geelong, and keep going west in the direction of Colac. Late in August 2006, soon after I had watched a magistrate commit Robert Farquharson to stand trial before a jury on three charges of murder, I headed out that way on a Sunday morning, across the great volcanic plain.

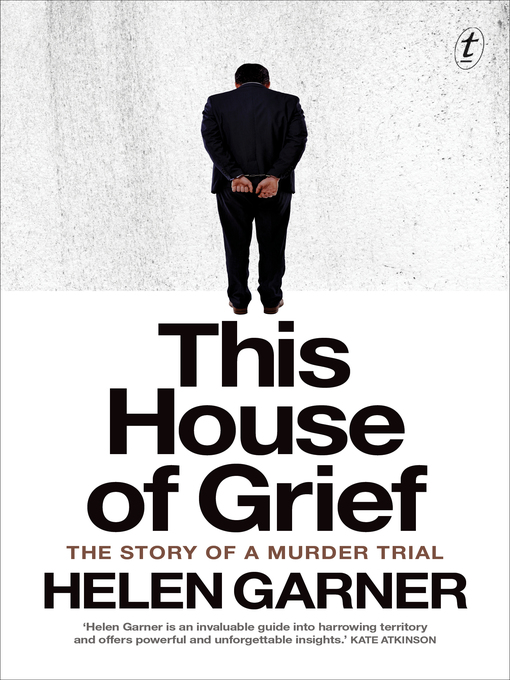

On the evening of 4 September 2005, Father's Day, Robert Farquharson, a separated husband, was driving his three sons home to their mother, Cindy, when his car left the road and plunged into a dam. The boys, aged ten, seven and two, drowned. Was this an act of revenge or a tragic accident? The court case became Helen Garner's obsession. She followed it on its protracted course until the final verdict.

In this utterly compelling book, Helen Garner tells the story of a man and his broken life. She presents the theatre of the courtroom with its actors and audience – all gathered to witness to the truth – players in the extraordinary and unpredictable drama of the quest for justice.

This House of Grief is a heartbreaking and unputdownable book by one of Australia's most admired writers.

PRAISE FOR THIS HOUSE OF GRIEF

'This House of Grief will have your heart in your mouth.' Ramona Koval, Best Books of the Year, Weekend Australian

'Tender and electrifying. This House of Grief is Helen Garner's masterpiece.' Saturday Paper

'The twists and turns of this true-crime story are, in Garner's hands, more engrossing and dramatic than any thriller. Really, this is the kind of book you'll devour in one go.' Age

'A rigorous, compassionate meditation on the unfathomable depths of human behaviour.' New York Times